We think of the deep ocean as a place of darkness. But oceanologist Edie Widder has discovered it is full of lights – thanks to its many bioluminescent creatures!

Have you ever seen a firefly glowing in the night? The light that fireflies (and other living organisms) make is called “bioluminescence.” As a PhD student studying luminescence, Edith Widder knew that there were many bioluminescent animals in the ocean. But it wasn’t until she had a chance to go 800 feet down into the ocean in a special diving suit that she realized just how much light there is. “I was hoping to see bioluminescence, but I was so unprepared for what I saw,” she says. “It was like fireworks! Just brilliant squirts and sparkles of neon blue and blue-green swirling all around me, and if I tapped the thrusters and moved there would be these explosions of light and sparks like blue embers!”

Dr. Widder went on to spend her career learning more about life deep in the open ocean, and especially its bioluminescence. “We knew very little about the ocean, because we didn’t have the tools to explore it. So I also spent a lot of my career developing tools to explore the ocean in new ways,” she adds.

Why do so many ocean creatures make light?

Many small creatures on earth survive by hiding. They burrow in the ground, hide in or behind trees or shrubbery or under rocks. In the open ocean, Dr. Widder points out, there is nowhere to hide. So long ago, as predators began to evolve, smaller life forms went down into the dark depths to hide. To survive there, they evolved enhanced vision and enhanced visual signals in the form of bioluminescence.

They use their built-in chemical lights to:

- find food, using their lights as a flashlight or in some cases, like the anglerfish, as lures to attract their prey

- attract mates, so they can find each other in a huge, dark area

- defend themselves, by releasing luminescent chemicals into the face of a predator to temporarily blind it and allow them to escape. Dr. Widder says that bioluminescence holds great promise for science and medicine: “These complex chemicals could be hugely beneficial, and we’ve barely begun to understand them.”

Tech Tools

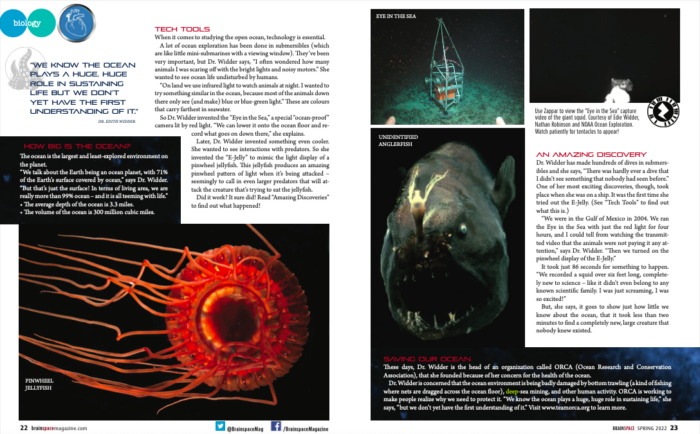

When it comes to studying the open ocean, technology is essential. A lot of ocean exploration has been done in submersibles (which are like little mini-submarines with a viewing window). They’ve been very important, but Dr. Widder says, “I often wondered how many animals I was scaring off with the bright lights and noisy motors.” She wanted to see ocean life undisturbed by humans. “On land we use infrared light to watch animals at night. I wanted to try something similar in the ocean, because most of the animals down there only see (and make) blue or blue-green light.” These are colours that carry farthest in seawater. So Dr. Widder invented the “Eye in the Sea,” a special “ocean-proof ” camera lit by red light. “We can lower it onto the ocean floor and record what goes on down there,” she explains.

Later, Dr. Widder invented something even cooler. She wanted to see interactions with predators. So she invented the “E-Jelly” to mimic the light display of a pinwheel jellyfish. This jellyfish produces an amazing pinwheel pattern of light when it’s being attacked – seemingly to call in even larger predators that will attack the creature that’s trying to eat the jellyfish. Did it work? It sure did! Read “Amazing Discoveries” to find out what happened!

An Amazing Discovery

Dr. Widder has made hundreds of dives in submersibles and she says, “There was hardly ever a dive that I didn’t see something that nobody had seen before.” One of her most exciting discoveries, though, took place when she was on a ship. It was the first time she tried out the E-Jelly. (See “Tech Tools” to find out what this is.) “We were in the Gulf of Mexico in 2004. We ran the Eye in the Sea with just the red light for four hours, and I could tell from watching the transmit- ted video that the animals were not paying it any attention,” says Dr. Widder. “Then we turned on the pinwheel display of the E-Jelly.” It took just 86 seconds for something to happen. “We recorded a squid over six feet long, completely new to science – like it didn’t even belong to any known scientific family. I was just screaming, I was so excited!” But, she says, it goes to show just how little we know about the ocean, that it took less than two minutes to find a completely new, large creature that nobody knew existed.