A new dawn broke 65 million years ago. That’s when a 15-kilometre asteroid slammed into Earth, rendering 75 per cent of its plants and animals extinct.

But soon, the acid rain that followed stopped, and the Sun peaked through a decade-long haze of dust. The Mesozoic Era was over, taking with it the reign of the mighty dinosaurs. What would this post-apocalyptic landscape bring, and how many kinds of giant penguins waddled around it?

Millions of years later amateur paleontologist Leigh Love is helping answer that question. This past August, she uncovered some especially large bird bones at a New Zealand dig site, Waipara Greensand. Rich with ancient remains of giant penguins (four other species have been discovered there over the last three decades), this fossil bed is the place to find clues into this flightless bird’s mysterious past.

Yet Love’s discovery is unique: its official scholarly paper, published in the paleontology journal Alcheringa, reveals that these bones are “the oldest of the giant early Cenozoic penguins.” Their classification, Crossvallia waiparensis, is the first of its kind, and most closely resembles a penguin species discovered in Antarctica, Crossvallia unienwillia. Remember when Antarctica was attached to present-day New Zealand 80 million years ago?

Love’s bones indicate that waiparensis was huge. At 5’2” and weighing between 155-175 pounds, this penguin-beast would cast a large shadow over the average fourth-grade human, beating our present-day biggest specimen, the Emperor penguin, for the title of Largest Oval-Shaped Animal We Want to Hug.

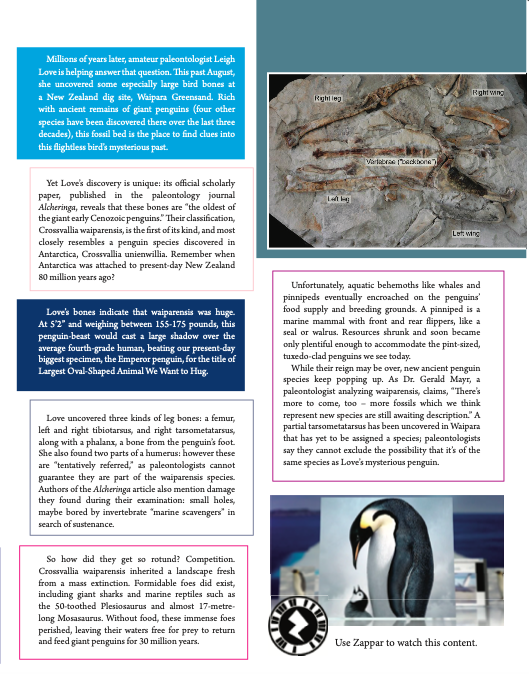

Love uncovered three kinds of leg bones: a femur, left and right tibiotarsus, and right tarsometatarsus, along with a phalanx, a bone from the penguin’s foot. She also found two parts of a humerus: however these are “tentatively referred,” as paleontologists cannot guarantee they are part of the waiparensis species. Authors of the Alcheringa article also mention damage they found during their examination: small holes, maybe bored by invertebrate “marine scavengers” in search of sustenance.

So how did they get so rotund? Competition. Crossvallia waiparensis inherited a landscape fresh from a mass extinction. Formidable foes did exist, including giant sharks and marine reptiles such as the 50-toothed Plesiosaurus and almost 17-metre- long Mosasaurus. Without food, these immense foes perished, leaving their waters free for prey to return and feed giant penguins for 30 million years.

Unfortunately, aquatic behemoths like whales and pinnipeds eventually encroached on the penguins’ food supply and breeding grounds. A pinniped is a marine mammal with front and rear flippers, like a seal or walrus. Resources shrunk and soon became only plentiful enough to accommodate the pint-sized, tuxedo-clad penguins we see today.

While their reign may be over, new ancient penguin species keep popping up. As Dr. Gerald Mayr, a paleontologist analyzing waiparensis, claims, “There’s more to come, too – more fossils which we think represent new species are still awaiting description.” A partial tarsometatarsus has been uncovered in Waipara that has yet to be assigned a species; paleontologists say they cannot exclude the possibility that it’s of the same species as Love’s mysterious penguin.