What is Shark Week

Shark Week highlights the diversity, behavior, and conservation efforts surrounding these apex predators. It serves as a platform to raise awareness about the importance of shark conservation and dispel common myths and misconceptions about these misunderstood creatures. Shark Week has become a cultural phenomenon, captivating audiences worldwide and fostering a deeper appreciation for the beauty and complexity of the marine world.

•

Shark week is July 7th to July 14th, 2024! In honour of Shark Week, we want to share a collection of our most popular shark-related articles from our past issues of Brainspace magazine.

•

Newly Discovered Sharks

Laila’s Lanternshark (Etmopterus Lailae)

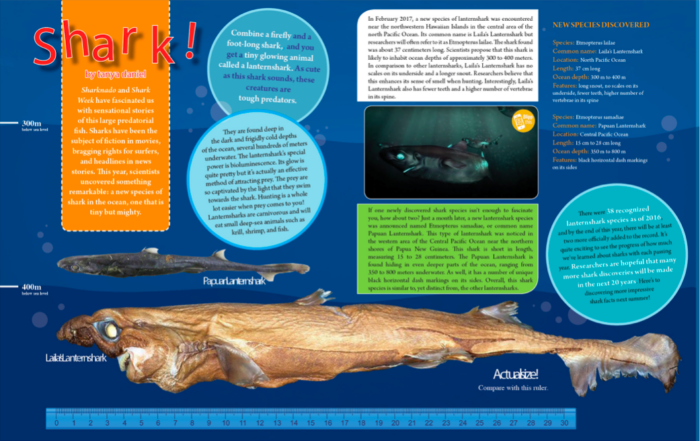

In February 2017, scientists uncovered something remarkable: a new species of shark in the ocean, one that is tiny but mighty. A new species of lanternshark was encountered near the northwestern Hawaiian Islands in the central area of the North Pacific Ocean. Its common name is Laila’s Lanternshark, but researchers will often refer to it as Etmopterus Lailae. The shark found was about 37 centimetres long. Scientists propose that this shark is likely to inhabit ocean depths of approximately 300 to 400 metres. In comparison to other lantersharks, Laila’s Lantershark has no scales on its underside and a longer snout. Researchers believe that this enhances its sense of smell when hunting. Interestingly, Laila’s Lanternshark also has fewer teeth and a higher number of vertebrae in its spine.

Papuan Lanternshark (Etmopterus Samadiae)

If one newly discoveres shark species wasn’t enough to fascinate you, how about two? Just a month later, a new lanternshark species was announced, named Etmopterus Samadiae, or the common name Papuan Lanternshark. This type of lanternshark was noticed in the western area of the Central Pacific Ocean near the northern shores of Papua New Guinea. This shark is short in length, measuring 15 to 28 centimetres. The Papuan Lanternshark is found hiding in even deeper parts of the ocean, ranging from 350 to 800 metres underwater. As well, it has a number of unique black horizontal dash markings on its sides. Overall, this shark species is similar to, yet distinct from, the other lantersharks.

.

A Fish Story

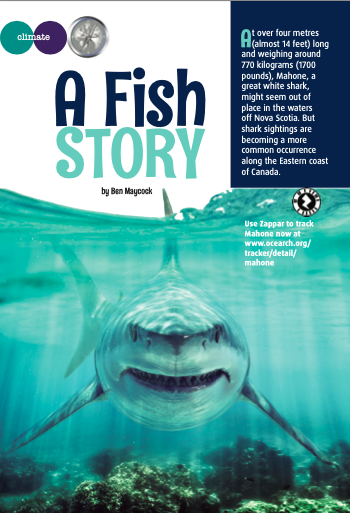

At over four metres (almost 14 feet) long and weighing around 770 kilograms (1700 pounds), Mahone, a great white shark, might seem out of place in the waters off Nova Scotia. But shark sightings are becoming a more common occurrence along the Eastern coast of Canada.

Climate change may be responsible for the increased sightings, however research is in its early stages. Recent studies involving tiger sharks in the North Atlantic have shown that ocean warming is affecting them, causing them to migrate as far north as Cape Cod. In 2018 a tiger shark was caught as far north as Halifax, but that may have been result of the creature being carried off course in a warm eddy off the Gulf Stream.

Compared to other ocean species, some sharks are not as affected by changes in the temperature of the water. In fact, they can tolerate quite a range of temperatures. White sharks, for example, may prefer temperatures above 12 degrees Celsius, but they have been detected in waters as cold as 2 degrees Celsius and as warm as 27 degrees Celcius! It could be that the sharks have always been there but we just were not fully aware of their presence. Over the past 10 to 15 years, tagging and tracking technology has greatly improved.

“The tracking technology is fairly new and equipment like Pop-up Satellite Archival Tags (PSAT’s) and Acoustic Telemetry Tags and Acoustic receivers have greatly helped us to understand shark distribution better than in the past,” says Warren Joyce, an aquatic fisheries technician with the Department of Fisheries and Oceans. “Researchers in the past were limited by the technology of the time and didn’t really track shifts in distribution of shark populations until more recently.”

It also may be that there are just more sharks now, which is great news. White sharks are listed as an endangered species in both Canada and the U.S. meaning they cannot be harvested. This has likely led to the white shark numbers returning to a more natural population level.

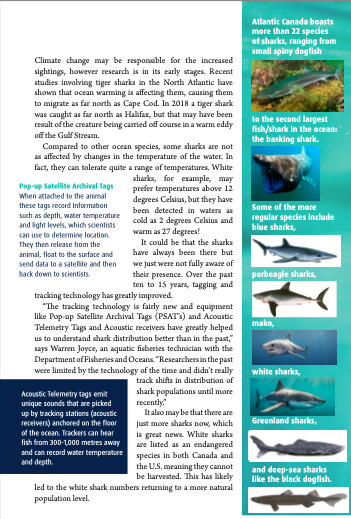

Atlantic Canada boasts more than 22 species of sharks, ranging from small spiny dogfish to the second largest fish/shark in the ocean: the basking shark. Some of the more regular species include blue shark, porbeagle sharks, white sharks, Greenland sharks, and deep-sea sharks like the black dogfish.

.

Mysterious MEGS

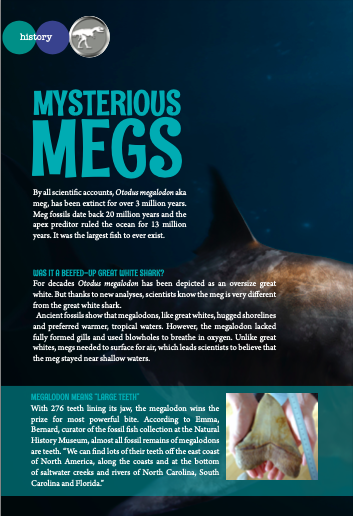

By all scientific accounts, Otodus megalodon aka meg, has been extinct for over 3 million years. Meg fossils date back 20 million years and the apex preditor ruled the ocean for 13 million years. It was the largest fish to ever exist.

WAS IT A BEEFED-UP GREAT WHITE SHARK?

For decades Otodus megalodon has been depicted as an oversize great white. But thanks to new analyses, scientists know the meg is very different from the great white shark. Ancient fossils show that megalodons, like great whites, hugged shorelines and preferred warmer, tropical waters. However, the megalodon lacked fully formed gills and used blowholes to breathe in oxygen. Unlike great whites, megs needed to surface for air, which leads scientists to believe that the meg stayed near shallow waters.

MEGALODON MEANS “LARGE TEETH”

With 276 teeth lining its jaw, the megalodon wins the prize for most powerful bite. According to Emma, Bernard, curator of the fossil fish collection at the Natural History Museum, almost all fossil remains of megalodons are teeth. “We can find lots of their teeth off the east coast of North America, along the coasts and at the bottom of saltwater creeks and rivers of North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida.”

WHERE DID IT GO?

The extinction of the megalodon is still a mystery. While paleontologists do know that shallower oceanic zones were dramatically cooling around 3.5 million years ago, there is no evidence of why the giant disappears from the fossil record. Marine mammals were less abundant, and the newly evolved great white may have been more agile and a better competitor for food to its larger cousin. But there’s no way to prove the megalodon’s extinction. This may explain why many refuse to believe the 50-foot predator could have just disappeared. Some suggest that for several epochs, megalodons have retreated to deep ocean craters and – to this day – remain in these unexplored regions of the world.

COULD A MEGALODON STILL EXIST?

‘If an animal as big as megalodon still lived in the oceans we would know about it.’ says Emma Bernard, curator of the fossil fish collection at the Natural History Museum. Analysis of megalodon remains indicate that it was a warm-blooded creature that needed to swim constantly in order to generate enough body heat. The intensity of movement would mean that a 50-foot megalodon would need to eat about 18 pounds of meat per day to survive.

“If it existed, we’d see large bite marks in whales, dolphins or other large fish,” says Emma. A megalodon would not likely have retreated to frigid deep waters with an average temperature of 4°C – brrrrr. It would have been too difficult for it to breathe and we know that ocean bottom creatures have to survive on teeny scraps of meat, which surely wouldn’t satisfy the diet of a megalodon.

.

Megalodons vs. Blue Whales

In true time, these two creatures could never battle! But hypothetically, who would rule?

Use the Zappar app to scan the image below for the answer!